The Early Years

Before delving into the symbolism of the drawings that have survived, it is important to take a moment to mention the ones that have not. Brooks’ memoirs often refer to her early experiences with drawing, and have proved to be an essential or invaluable resource. According to her text, from an early age, creating art, drawing, or even the display of imagination or creativity, was grounds for punishment from her mother. In writing about her earliest memories of drawing around six years old, Romaine recalls the following:

"One day, after I had arranged them [my drawings] on the floor, against the wall, my mother passed by. She stooped down and, looking at the collection, picked them up and carried them off to her room. I never saw them again, and fro[m] that time I was forbidden to draw."1

Her mother was not only unsupportive, but stymied all her efforts to use her personal talents. The fear of punishment could not overcome her desire to draw however, and she continued her artwork in secret. Brooks recalls, “Whenever I sketched, it was on the sly. Pencil and pads were quickly hidden when the jingling of my mother’s chatelaine warned me of her approach.”2 Later, when her mother sent her off to the various boarding schools that made up her childhood education, her artwork flourished as her mother’s watchful eye was too far away to prevent her talents from blossoming.

Early Drawings

During one particular instance at Mademoiselle Bertin’s Private Finishing School for Young Ladies in Switzerland, Brooks reminisces fondly about a teacher who encouraged her abilities:

"I have already mentioned that it was my habit to draw sketches during lecture time. Not only had I never been admonished by my teachers for doing so but frequently had won their approbation. Mademoiselle Tobet was no exception, and at times she would ask to see my copy-books.” 3

As her pictorial gifts became more evident at these schools, her instructors put her talents to use. While studying at a convent in Italy she mentions that she was, "promoted to post of all-round draughtsman,"4 and asked to design such figures as cardboard angels for the convent theater. Of this same period in her life, she proudly recalls, "The highest honor came by way of insinuation that when received into the sisterhood I should be allowed to co-operate as drawing teacher."5 This aspiration would remain unrealized as Brooks never fully converted to Catholicism.

"No Pleasant Memories"

Quotes from the unpublished memoirs of Romaine Brooks

While her childhood was filled with encouragement and praise from her teachers and peers, Brooks dreaded the instances when she was forced to return home. As the youngest of three children, Brooks was virtually ignored within her family unit. Her father, Major Harry Goddard, left within the first year after her birth and her older sister ceases to exist in the pages of Brooks’ memoirs. Due to the lavish and transient lifestyle of Romaine’s mother, Mrs. Ella Goddard, Romaine was raised by a variety of different attendants in hotels across Europe. Her mother endlessly doted on her eldest sibling, a mentally-unstable and violent brother named, St. Mar. Romaine was often obliged to care for him but his eccentricities made it an extremely disagreeable task. Ella’s frustration with her son’s illness was frequently released through rage toward Romaine. It was as if Ella resented Romaine for having the intelligence that St. Mar lacked. In a chapter titled, “His Keeper,” Brooks describes the relationship between herself and the two family members with whom she was forced to live.

"I think my brother was generally aware of my presence. He felt my sympathy and accepted it in a form so comfortably remote. He was to me the less fearful of the two strange creatures that encircled me; moreover, in his crazy fashion, his was the only protection I could hope to find." 6

Understanding her strained relationship with these, “two strange creatures,” contributes to the interpretation of the continuous line drawings that were left in the national collection. The “encircling” entrapment of her home environment is reflected in the encompassing lines of her contour drawings.

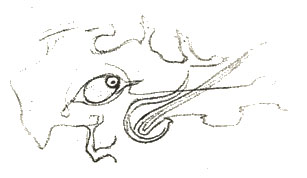

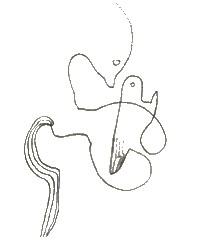

The earliest examples of Romaine’s surviving drawings date from 1889-1891 when the artist was around sixteen years of age.7 L’Oeil (The Eye) (c. 1889; above slideshow) depicts the watchful eye of her mother who invariably haunted her even when she was away from home. Her untrained lines are sporadic and lack consistent strength or confidence reflecting her youthful personality that was hindered by an overbearing parent. In La Femme et l’enfant (The woman and Child) (c.1889; above slideshow), the figure of a woman and a child are intertwined by the unbreakable grip of the mothers arms around the child’s legs. It can be read as an obvious allusion to Brooks’ childhood struggle for independence. In a comprehensive assessment of Brooks’ drawings written in the 1997 Women’s Art Journal, art historian Catherine McNickle Chastain highlights this work and comments further on the interconnectedness of the figures. She writes, “More noticeably than in any of the later works, the lines that form the bodies of the two figures merge, creating a Siamese twinlike effect that suggest the utter impossibility of the effort.” 8 In another work titled, L’oiseau et son enfant (Bird and its child) (c.1891; above slideshow), Brooks depicts a mother bird as it lovingly cares for its young fledgling. The image suggests Romaine’s possible yearning for a closer and more loving relationship with her mother.

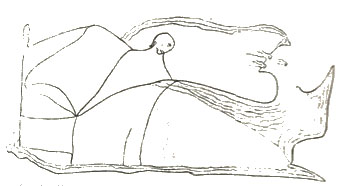

While the majority of these early images focus on the tribulations of living with her mother’s idiosyncrasies, the final image that survives from this period is thematically different. It is titled, L’homme qui voit sa mort (The Man Who Sees His Death) (c. 1891; above slideshow).This image has an overwhelming feeling of sadness as it depicts death rising up to challenge God. One critic refers to it as, "an amazingly impressive, descriptive drawing within a composition that is masterful as a near-abstraction."9 While no further examples have survived of this theme from the same period, through passages from her memoirs it becomes obvious that Brooks’ preoccupation with death and otherworldly beings is not unique to this work. On the day of an extremely rare visit from her father to her school she wrote, "Before leaving… he spoke to me of my gift for drawing and of his admiration for Gustave Doré."10 Considering that her father compares her work to a nineteenth century German literary illustrator known for his engravings used to illustrate texts such as Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dante’s Divine Comedy , there must have been thematic semblances and striking similarities to his fantastical figures. In another instance, on the occasion of her best friend leaving school she wrote, “There was now plenty of time to draw sad drooping figures under equally sad,drooping willow trees; or if the mood demanded, Death and the Devil rocking the cradle of doomed infants.” 11 It also seems this type of imagery prevailed once she had left school and started living on her own as a young lady in Paris. Upon meeting an English artist working there, she wrote, "To show that I really belonged to the artists’ community I draw on his pad a series of devils and angels’ heads." 12 Given the evidence, I am led to assume that many of her drawings from her youth were extremely imaginative and dominated by themes of God, death, and fantasy. In studying the drawings that followed, these themes along with images of her ongoing struggle with her mother and her brother’s eccentricities, would continue to prevail through her work into the 1930s.

Footnotes

Brooks, Romaine. No Pleasant Memories, 6-7.↑

Brooks, No Pleasant Memories, 6-7.↑

Brooks, No Pleasant Memories, 94.↑

Brooks, No Pleasant Memories, 65.↑

Brooks, No Pleasant Memories, 65.↑

Brooks, No Pleasant Memories, 48.↑

The present location of these drawings is unknown and they only survive through photographs.↑

Catherine McNickle Chastain. “Romaine Brooks: A New Looks at Her Drawings.” Woman’s Art Journal Vol. 17 No. 2 (Autumn, 1996- Winter, 1997): 12. ↑

Breeskin, Romaine Brooks, 39.↑

Brooks, No Pleasant Memories, 29.↑

Brooks, No Pleasant Memories, 92.↑

Brooks, No Pleasant Memories, 113.↑